[Source: Ryan Randazzo, The Arizona Republic] – The lowly cyanobacterium isn’t much to look at, but the simple life form thought to have originally created the oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere could be on the verge of making another dramatic impact on the planet: transforming the oil business.

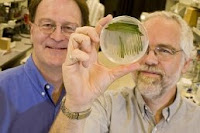

Arizona State University researchers are exploring how one of Earth’s smallest organisms may supplant its largest industry by growing bacteria to make diesel-engine fuel.

Energy company BP and Science Foundation Arizona partnered for the project.

Researchers are building “photobioreactors” to grow the bacteria, hoping to prove that the bacteria can be raised on a commercial scale, said Bruce Rittmann, director of the Center for Environmental Biotechnology at the ASU Biodesign Institute.

Bacteria have an advantage over other “biofuels” such as corn ethanol and soybean biodiesel, he said.

Not only do the bacteria contain a higher concentration of fats that can be burned for energy, but they grow faster than crops and can be continuously harvested.

“We have one (strain) with a high lipid content, and by promoting the right conditions, it can thrive and grow very fast,” Rittmann said.

Instead of needing fertilizer, which is costly and requires energy to produce, researchers hope to feed the bacteria the carbon dioxide released from electric power plants.

That is an increasingly popular idea in the energy industry, where carbon-dioxide emissions are getting increased scrutiny for their contribution to global climate change.

Arizona Public Service Co. already has had some success “feeding” the carbon dioxide from a natural-gas power plant to algae for biodiesel, and plans to test at a coal-fired plant.

Researchers around the globe are investigating both bacteria and algae because they have high energy potential, require little space to grow and can thrive in marginal water.

The bacteria being tested at ASU are similar to the algae tested by researchers at APS and elsewhere because they both use photosynthesis to convert sunlight to energy, but Rittmann said the bacteria have advantages over algae.

“Algae and bacteria both accumulate a lot of lipids, but they do so for different reasons,” he said. “When bacteria accumulate a lot of lipids, they do it when they are growing fast. That is ideal. Algae do the opposite, and produce high lipids when under stress, and are not growing very well.”

Other Arizona projects are focusing on algae, including: